Lawsplainer: Ninth Circuit Judge Makes The Case That Calling Up The National Guard Is A Decision Left To The President -- No Role For Judges.

Appeals Court blocks the District Court's Order about Portland with unsparing language in a powerful counterpoint to the squishy approach of the Seventh Circuit to the same issues in Chicago.

Three articles in one here today because yesterday’s decision by the Ninth Circuit in Oregon v. Trump packs a powerful punch.

In a 2-1 per curiam opinion, the Majority lambasted Portland District Judge Immergut in for claiming she gave “great deference” to the President’s factual determinations for activating the Oregon National Guard, but she hadn’t. In fact, she discounted the facts presented by the President, adopted her own views as to the facts on the ground, and then then substituted her judgement for his on the question of whether the enforcement of immigration law in Portland was possible. The Majority Opinion is very fact driven and repeatedly makes the point that Judge Immergut ignored or downplayed the significant volume of evidence about how ICE operations were being impacted by rioters — including having closed down the ICE processing center in Portland for three weeks in June and July.

Judge Ryan Nelson wrote a concurrence that went one step further. He advanced the view that the earlier Ninth Circuit panel in Newsom v. Trump about the California National Guard deployment was wrong in concluding that the President’s decision to deploy National Guard troops was reviewable by the judiciary. Because another panel of judges had already decided that the President’s decision was subject to judicial review on a “highly deferential” standard, the Oregon case panel was obligated to follow it. But Judge Nelson wrote separately to lay out why, in his view, the historical record and prior Supreme Court decisions point towards a different conclusion, i.e., that Congress meant for the President’s exercise of authority under Sec. 12406 to not be subject to court scrutiny — but rather it is up to Congress to take steps to address Presidential abuses of that authority.

The opinion in the Oregon case shows in so many ways how — as I said in this earlier article on Sunday — the Seventh Circuit dodged the key questions that undercut Chicago Judge April Perry’s TRO about Chicago ICE operations that the Seventh Circuit allowed to stand. That Court turned a blind eye towards Judge Perry’s approach which mirrored Judge Immergut’s in Portland, and concluded that she was not “wrong enough” — in legal terms her factual findings were not “clearly erroneous” — to justify setting aside her conclusions that were substituted for President Trump’s judgements on the facts in Chicago.

The Unsparing Chastisement of Judge Immergut by the Ninth Circuit.

As noted above, the Majority Opinion leaves very little standing of Judge Immergut’s factual analysis she used to justify her decision blocking the federalization of the Oregon National Guard, and the deployment of any federalized National Guard to assist in the enforcement of immigration law in Portland.

I was critical of Judge Immergut’s written opinion in an earlier article published in the immediate aftermath of her imposing a TRO, noting that she had “written into” the Ninth Circuit’s earlier opinion in the California case, Newsom v. Trump. By that I meant that she used what the Newsom panel identified as San Francisco Judge Charles Breyer’s errors in his TRO involving the California National Guard deployment as her guide for what she needed to find — and not find — to make her TRO stand-up where Judge Breyer’s had failed. Chief among them, she limited the scope of facts relevant to her decision to events in Portland just days before she granted the TRO. As the decision makes clear, dramatically limiting the extent of the violence she considered that had plagued the ICE operations in Portland long before the Administration began to emphasize Portland for immigration enforcement.

It seems clear that Judge Immergut was relying on the normal appellate review of her factual findings — that the Appeals Court will leave them in place unless they are “clearly erroneous.” Because the trial judge is deemed to have had a more clear view of the evidence and arguments made by the parties in open court, Appeals Courts are deferential to factual findings made by the trial judge given that appellate judges review such findings on a “cold” written record in a transcript. While appellate judges might disagree on certain factual determinations, they substitute their view for the trial judge’s decision only where the lower court is “clearly wrong” — a level beyond mere disagreement. In fact, the one dissenting Judge, Clinton appointee Susan Graber based her vote on this proposition — “We must defer to the district court’s factual findings unless they are clearly erroneous.” She based her dissent on the facts as found by Judge Immergut, and not the broader factual record presented by DOJ.

But the decisions by Judge Immergut were based almost entirely on affidavits and videos of protesters at the ICE facility. The Appeals Court judges could review those kinds of evidence in the same manner that they were reviewed by Judge Immergut. There is no basis for her to make “credibility” determinations on affidavits and videos better than the appellate judges. They can read and watch just the same as a district judge does.

More significantly, while Judge Immergut limited her review to the facts in the days just prior to the President’s invoking of his authority under Sec. 12406, the Ninth Circuit panel found no basis for her to have truncated her review in that way.

The following two passages sum up nicely the Majority’s view of Judge Immergut’s opinion:

Whether Defendants have shown a likelihood of success on the merits … turns on whether the President’s determination under § 12406(3), that he was “unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States,” “reflects a colorable assessment of the facts and law within a ‘range of honest judgment.’” (Newsom v. Trump)…. While the district court cited this highly deferential standard … it erred by failing to apply it. Instead, the district court substituted its own assessment of the facts for the President’s assessment of the facts. This is the opposite of the significantly deferential standard of review that applies to the President’s decision to invoke § 12406(3) and federalize members of the National Guard….

….

[T]he district court erred by determining that the President’s “colorable assessment of the facts” is limited by undefined temporal restrictions and by the district court’s own evaluation of the level of violence necessary to impact the execution of federal laws. Thus, the district court determined that it would apply Newsom’s deferential “colorable basis” standard to the facts “as they existed at the time [the President] federalized the National Guard….” The district court then discounted the violent and disruptive events that occurred in June, July, and August, including the resulting closure of the ICE facility for over three weeks in June and July … and focused on only a few events in September…. Thus, the district court discounted most of the evidence of events in Portland from June through September.

Section 12406 contains no such limitations. Instead, by its plain text, Sec. 12406(3) requires only a determination that “the President is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.” The statute delegates the authority to make that determination to the President and does not limit the facts and circumstances that the President may consider in doing so. Indeed, the inherently subjective nature of this evaluation demonstrates … [t]he President can, and should, consider the totality of the circumstances when determining whether he “is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.”

The Opinion then proceeds to go through the events from June to September in great detail, pointing out their significance — which Judge Immergut determined to be irrelevant because of the passage of time — to the determination that deployment of the National Guard in September was necessary to protect the immigration law enforcement personnel and federal property.

This particular part of the opinion is rather pointed in the degree to which the Appeals Court judges “upbraided” Judge Immergut for her transparent efforts to arrive at her preferred conclusion by a crimped reading of both the statute and the earlier opinion in Newsom.

Judge Nelson’s Well-Conceived Argument that Newsom Was Wrongly Decided.

I’ve written here previously that the Ninth Circuit’s decision as to whether “judicial review” was appropriate for a President’s invocation of Sec. 12406 was not so much the result of thoughtful legal analysis, but more so the result of the fact that the Newsom panel was going to reverse Judge Breyer under any standard of review, and the choice of a “highly deferential” standard was less controversial because it was not a complete surrender on the question of whether judicial review at an early stage in the case. This is very common at the appellate level — to decline to specify which standard of review is correct on the basis that the losing party would lose under any standard applied (de novo, clear error, abuse of discretion).

Judge Nelson recognizes that the Oregon panel’s hands are tied on the issue because the Newsom panel opted to use a “highly deferential” standard rather than take the more controversial position that the President’s exercise of discretion was not subject to review at all. But he wrote a separate Concurring Opinion to explain why he believes the Newsom panel’s decision — if even only by default — was incorrect as a historical and legal matter.

The ultimate conclusion reached by Judge Nelson is that if there authority granted to the President by Congress is abused in the sense that he’s activating the National Guard in circumstances not intended by Congress, the remedy for such abuses rests with Congress, not the Courts. He points to three historical cases decided by the Supreme Court, which the Court has never reconsidered, as pointing to that being the case.

I address the basics of his Concurring Opinion below, but lets first contrast that view with the view of the role of the judiciary as expressed by Judge Graber in her dissent:

The Founders recognized the inherent dangers of allowing the federal executive to wrest command of the State militia from the States. Congress authorized the President to deploy the National Guard only in true emergencies — to repel an invasion, to suppress a rebellion, or to overcome an inability to execute the laws. 10 U.S.C. § 12406. Congress did not authorize deployment in merely inconvenient circumstances, and Congress unquestionably did not authorize deployment for political purposes. Article III commands that we enforce those limits.

….

We have come to expect a dose of political theater in the political branches, drama designed to rally the base or to rile or intimidate political opponents. We also may expect there a measure of bending—sometimes breaking—the truth. By design of the Founders, the judicial branch stands apart. We rule on facts, no on supposition or conjecture, and certainly not on fabrication or propaganda.

I think Justice Barrett had a phrase for this point of view — the “Imperial Judiciary” she called it when stridently rebutting Justice Jackson’s view of judicial authority to second-guess Presidential actions.

Judge Nelson’s analysis begins with a review of Martin v. Mott, an Supreme Court decision in 1827 that I’ve referenced on this subject many times. Mott was a NY state militiaman who refused to report when called upon by the NY Governor at the start of the War of 1812, and was later court-martialed. He attempted to defend himself in a related civil court proceeding by claiming that President Madison had not properly adjudged that an invasion or threat of invasion was happening under the Militia Act of 1795, which is a predecessor statute to Sec. 12406 used by President Trump. A lower court agreed with Mott, and that decision made its way to the Supreme Court, which reversed. The key passage from the Supreme Court’s decision is quoted by Judge Nelson:

“[T]he authority to decide whether the exigency has arisen, belongs exclusively to the President, and that his decision is conclusive upon all other persons.”

Some, including the Seventh Circuit, question the extent to which the reference in Mott to “all other persons” should be read to include the courts. That Seventh Circuit determined that Mott did not preclude judicial review by noting that Mott himself was a subordinate in the Executive branch in a time of war, and as such he and others similarly situated could not be allowed to make their own determinations about whether state militias were properly called into federal service.

But Judge Nelson backed his view that Mott precludes judicial review with the second case relied upon by DOJ in arguing that the President’s discretion is not reviewable — Luther v. Borden. This was another case under the Militia Act of 1795, where President Tyler had decided against activating militia troops at the request of the Rhode Island Governor to help put down Dorr Rebellion against the Rhode Island state govenrment. The rebellion was initiated in an effort to replace the existing Rhode Island government with a new government based on a newly passed state charter.

While not having to address action by President Tyler, the Supreme Court did comment on the Militia Act of 1795 and the discretion given to the President to respond with militia troops “in case of an insurrection in any State against the government thereof.” In considering the Act, the Court commented:

[T]he power of deciding whether the exigency had arisen upon which the government of the United States is bound to interfere is given to the President.

….

After the President has acted and called out the militia, is a Circuit Court of the United States authorized to inquire whether his decision was right? Could the court, while the parties were actually contending in arms for the possession of the government, call witnesses before it and inquire which party represented a majority of the people? If it could, then it would become the duty of the court (provided it came to the conclusion that the President had decided incorrectly) to discharge those who were arrested or detained by the troops in the service of the United States or the government which the President was endeavouring to maintain. If the judicial power extends so far, the guarantee contained in the Constitution of the United States is a guarantee of anarchy, and not of order.

So the Supreme Court’s language in Luther expressly considered — and rejected — the authority of federal courts to second-guess a President’s decision under the Militia Act of 1795 to activate state militias.

Judge Nelson then turned to the Supreme Court’s decision in Sterling v. Constantin in 1932, the case from which the Newsom panel had taken the language about a Presidential exercise of authority needing a “colorable basis in fact” and the exercise of discretion being “within a permitted range of honest judgment” to find a limited though highly deferential form of judicial review for invoking Sec. 12406.

Judge Nelson observes that Sterling involved the powers of the Governor of Texas under a Texas statute, and not the President’s authority over the militias as conferred upon him by Congress. The Supreme Court in Constatin did cite its own holding in Mott by analogy when determining the review-ability of the Governor’s exercise of discretion. But whatever limits on review might be found in federal law or the Constitution with regard to the President is not going to be gleaned from a parsing of the statutes in Texas with regard to the Governor.

By virtue of his duty to “cause the laws to be faithfully executed,” the executive is appropriately vested with the discretion to determine whether an exigency requiring military aid for that purpose has arisen. His decision to that effect is conclusive. That construction, this Court has said, in speaking of the power constitutionally conferred by the Congress upon the President to call the militia into actual service, “necessarily results from the nature of the power itself, and from the manifest object contemplated.” The power “is to be exercised upon sudden emergencies, upon great occasions of state, and under circumstances which may be vital to the existence of the Union.” Martin v. Mott, 12 Wheat.19, 25 U. S. 29-30. Similar effect, for corresponding reasons, is ascribed to the exercise by the Governor of a state of his discretion in calling out its military forces to suppress insurrection and disorder.

The phrases a “colorable basis in fact” and “within a permitted range of honest judgment” as used in Sterling have nothing to do with the President’s discretionary finding that an exigency requiring military aid has occurred. According to Judge Nelson, the Newsom panel’s reliance on that language to find a basis for judicial review was incorrect. The Supreme Court said in both Mott and Luther that the exercise of discretion is conclusive on “all others” including courts.

As noted above, Judge Nelson’s view is that it is up to Congress to either 1) amend Sec. 12406 to make itself understood if it does not agree with Mott, Luther, and Sterling, and/or 2) use its own constitutional authority to addresses abuses of the discretion it conferred on the President where it finds that to be the case.

Finally, Judge Nelson said the language in Mott and Luther are the words of the Supreme Court. While that Court can alter and/or abandon its prior view, lower courts are bound by those holdings until changed by the Supreme Court or addressed in legislation by Congress.

Distinguishing The Squish Approach of the Seventh Circuit.

The criticisms of the Seventh Circuit’s decision leaving part of Judge Perry’s TRO in place and avoiding some of the most consequential decisions was the subject of much discussions in the recent Spaces discussion on X on Sunday night. You can find a recording https://x.com/McAdooGordon on X.

Since this article has become quite long, I’m going to truncate this third subject a bit. You can find many of my criticisms in the article from this past weekend that is linked above.

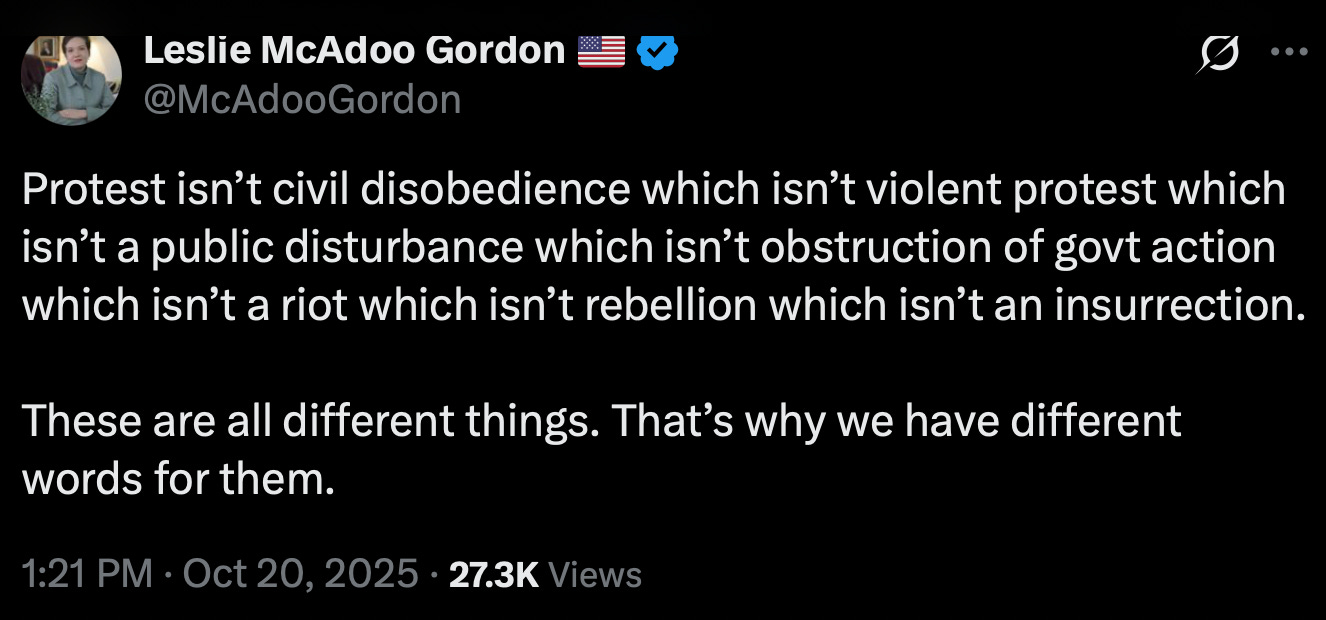

But I think this post by Leslie McAdoo-Gordon is quite instructive on where the Seventh Circuit’s decision to allow Judge Perry’s TRO to stand makes little sense:

The point made by Leslie is that “opposition” to enforcing federal law — and deporting illegal aliens is enforcement of the law as passed by Congress, including with Democrat votes — happens along a spectrum. While “public protesting” is protected by the First Amendment, pretty much every step taken beyond mere protesting is not covered. Everything beyond mere protesting is a violation of the law and can lead to police action against you. If the “regular forces” available to the President aren’t sufficient to curb everything beyond mere protesting, the issue arises as to who gets to decide if the President can employ the National Guard.

The statute says the President.

Judge Perry said “Yes, the President. Unless I disagree, in which case I get to decide.”

A point made by the Seventh Circuit is that the intermittent violence at the Chicago facility didn’t rise to the level of “rebellion” as that term has been historically used. Nor was the level of violence such that ICE was unable to conduct operations to enforce immigration law.

Those were the conclusions of District Judge Perry, and the Seventh Circuit held they were not “clearly erroneous” — even if “error” they weren’t such bad errors that she should be prevented from commandeering the Illinois and Texas National Guard at the urging of the Governor of Illinois and Mayor of Chicago.

Maybe just a little wrong, but not too much wrong.

But she has taken over command by virtue of her TRO telling the Commander in Chief, acting through the Secretary of War, that he can’t determine how those troops are to be used.

Judge Perry did what the Ninth Circuit chastised Judge Immergut for doing. Rather than simply take the “factual basis” as offered by the President and making a determination whether the President’s justification met the “deferential standard” being employed — at least for now — Judge Perry made the proceedings a “battle of addidavits” where she weighed what the President offered as facts against what the Illinois and Chicago offered as facts, and decided that she liked the locals version of events better than she liked the feds version of events.

The Seventh Circuit??

“Well, as long as she’s not too wrong … good enough for us.”

She not only did that however, she made “credibility” judgements with respect to 2 of the 3 affidavits offered by DOJ. In one the declarant provided information about the number of violent incidents that had led to arrests, and the number of protesters arrested during those violent incidents.

But Judge Perry found a “lack of candor” by that declarant because he had not further informed he that in two of those cases a federal grand jury had declined to return indictments.

I guess that was “too wrong” for her.

In a second incident, Judge Perry discounted a declaration from a Natioanl Guard Official coordinating the need for National Guard assistance that stated that a request for additional security had been made for the Federal Courthouse. Judge Perry questioned government attorneys during the hearing, stating she had asked the US Marshal, who provides security for the Courthouse, and she was told no such request had been made. She ordered the Government to provide the basis for having made such a claim.

The official involved explained in a subsequent declaration that the information was passed to him by another individual, and the second individual had specified the request for additional security at the “Federal Plaza” in downtown Chicago. A reference to a “federal plaza” is often to general area that includes a Federal Building and sometimes a separate Federal Courthouse in direct proximity to each other. The Official explained that after the Court raised the issue, the second individual who had passed the information to him said “Federal Plaza” but had no request specific as to the Federal Courthouse, and the declarant himself mistakenly concluded the request was for both buildings, including the Courthouse.

Judge Perry used that miscommunication as a basis to discount the entirety of that individuals declaration about the need for security at federal buildings.

After all, she had given the Government 48 hours to gather all these facts in a flawless fashion.

The Government has now filed an application with the Supreme Court to Stay Judge Perry’s TRO. Briefing on that motion is now complete and SCOTUS could solve all these problems quickly — maybe it has done so while I’ve been writing this.

But, the bottom line for Judge Perry’s opinion, now endorsed by the Seventh Circuit, is that it has two principle findings:

Unless a Civil War has broken out, some level of “executing the laws of the United States” remains possible so the National Guard can never be called upon to assist the “regular forces” in doing so.

The phrase “regular forces” is actually a reference to the active duty Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force, and unless the President has used all the resource available to him from the War Department and still failed to execute the laws, he cannot call up the National Guard to assist.

Well, I guess that’s okay as long as she isn’t too wrong.

At least in the Seventh Circuit.

Frankly, I find that these judges have a preconceived, political opinion that they wish to enforce, and will search high and low, misinterpreting and misrepresenting laws in order to come to their ruling. I’m tired of these judges deciding that they are not judges, but rather, are the President.

The “king” has shown herculean restraint in deferring to the idiots O’Biden appointed. There may come a time when lives are at stake and decisions can’t wait on the slow walk of the judicial branch.